The Crone’s Tarot: A Materialist Feminist’s Menopausal Adventure | by Dr V L McMahon

"An old woman’s lack of regular intercourse might mean that poisonous gas would build up in the womb and dissipate through bodily orifices, such as generating deadly eye beams to emanate and blind others."

The Origins of the Shakespeare Menopause Project

Twelve years ago, I decided to realise a lifetime’s obsession by writing a book — an academic book, to be precise. I knew that it would take at least a decade of research conducted piecemeal in those scarce and precious moments outside of raising a family and working a demanding fulltime job (not in academe). I knew that I could make it happen: I don’t like to be told ‘‘you can’t.’’ When people dubiously asked me what it would be about, I told them that it would be a book that would explore menopause through the eyes of five of Shakespeare’s tragic female characters. I managed to pitch my idea to a reputable academic press but one of the anonymous peer reviewers made no bones about the fact that he thought (and I’m sure it was a male) that my thesis was rubbish. “Women didn’t have menopause in Shakespeare’s time,” he said, regardless of the fact that I had documented hundreds of pages of medio-historical, classical, literary, mythological, religious and socio-cultural evidence to argue that they, of course, did. Although history had not yet given it a medical term and women themselves were yet to write of their own bodily experiences (that would come later in history), females did experience physiological and psychological changes that came with an ageing body. This is what I call the ‘proto-menopause.’

I argue that, at its core, the ageing woman troubled the sociocultural order because her value to the community became ambiguous once her reproductive abilities had come to an end. She was viewed as a drain on precious community resources and feared for her tendency to speak her mind – especially if widowed or unmarried. This fear and ambivalence were ‘read’ through her body itself. As ‘woman’ in the early modern period was defined by her womb, uterine changes were invariably read as pathological, and these ‘diseases’ fed into and bolstered archetypes about the old woman that had existed since classical times. For instance, the womb was said to crave semen as a sweet treat to keep it from escaping the body proper to cause harm to others. An old woman’s lack of regular intercourse might mean that poisonous gas would build up in the womb and dissipate through bodily orifices, such as generating deadly eye beams to emanate and blind others. This also resulted in the idea of the vampiric nocturnal witch – the nightmare – who would use spells to hypnotise young men so that she could suck their blood and seminal fluid. The ageing woman’s uterus was believed to spontaneously generate monsters, snakes, worms, stones, vermin and terrifying lumps of living flesh called ‘moles’. The origins of the archetypal Witch, oversexed Crone, Gorgon, Gossip, Scold, Hag, and Harpy stemmed from a very real belief that a woman’s ageing body was the dangerous etiological site of disease, contagion, malefic magic, and environmental catastrophe. These archetypes of the ageing female body had very real, often fatal implications for the woman herself. An ageing woman could have her body beaten, branded, mutilated, driven from her home into penury and starvation, pelted in stocks, forced to wear torturous implements, dunked in rivers, hanged, or burned alive. It is no accident that the vast majority of women condemned as witches in Europe were older post-menopausal women. In other words, our ongoing revulsion of the older woman’s body and sexuality has its origins deep within the history of folklore, mythology, natural philosophy, religion, and the medical profession. Shakespeare was simply drawing on his knowledge of this ancient tradition of viewing the older woman and her body as being demonic, unnatural, disease-ridden, and dangerous.

On the basis of that singular peer review, even though the two others had been enthusiastic and accepting, my book was rejected. “Here we go again,” I thought to myself, “the entire somatic experience of our sex being overlooked with a single dismissive gesture (probably by an ageing man)”. Finally accepted by a wonderful female editor at Palgrave MacMillan, the result was Shakespeare, Tragedy and Menopause: The Anxious Womb published in 2022.

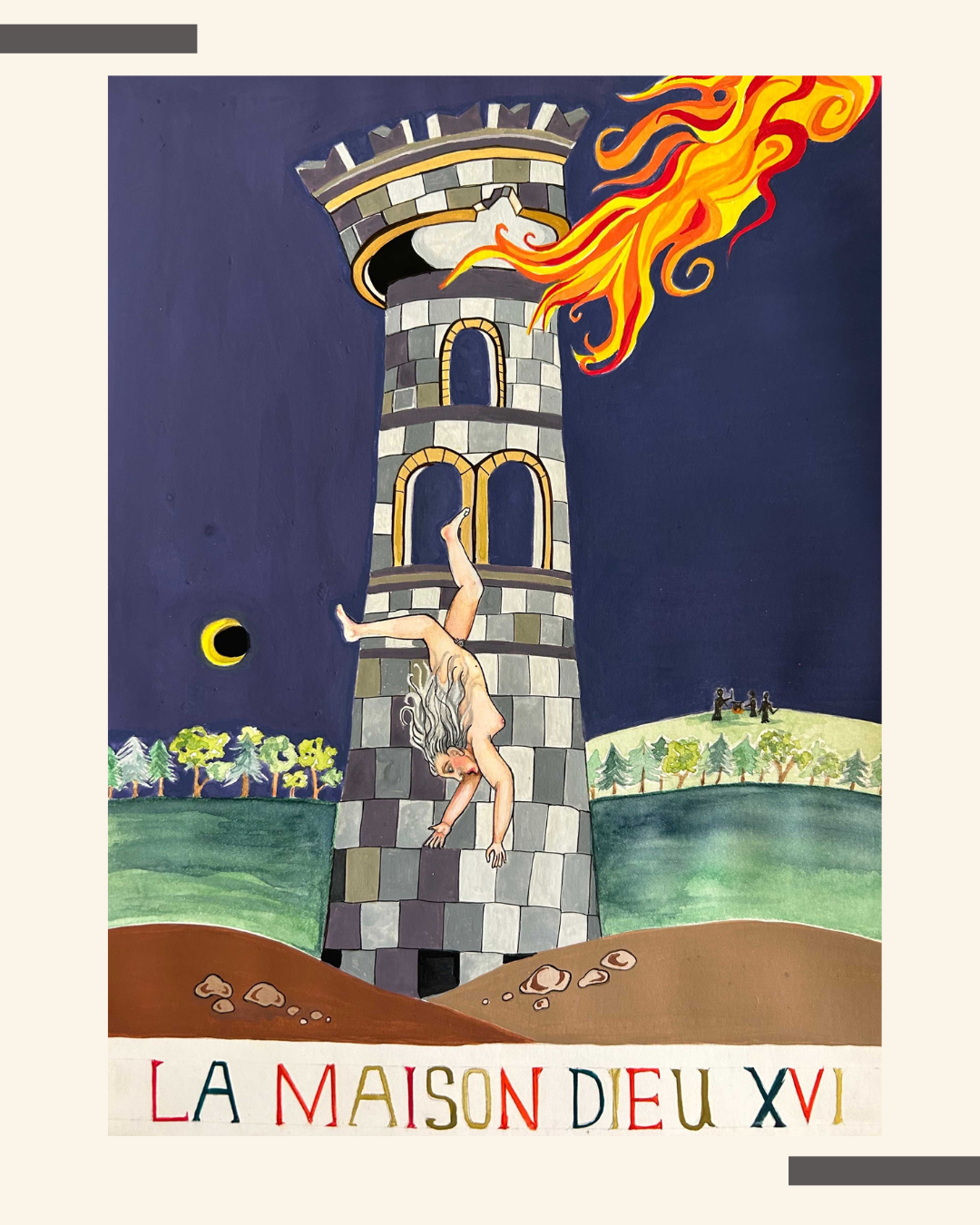

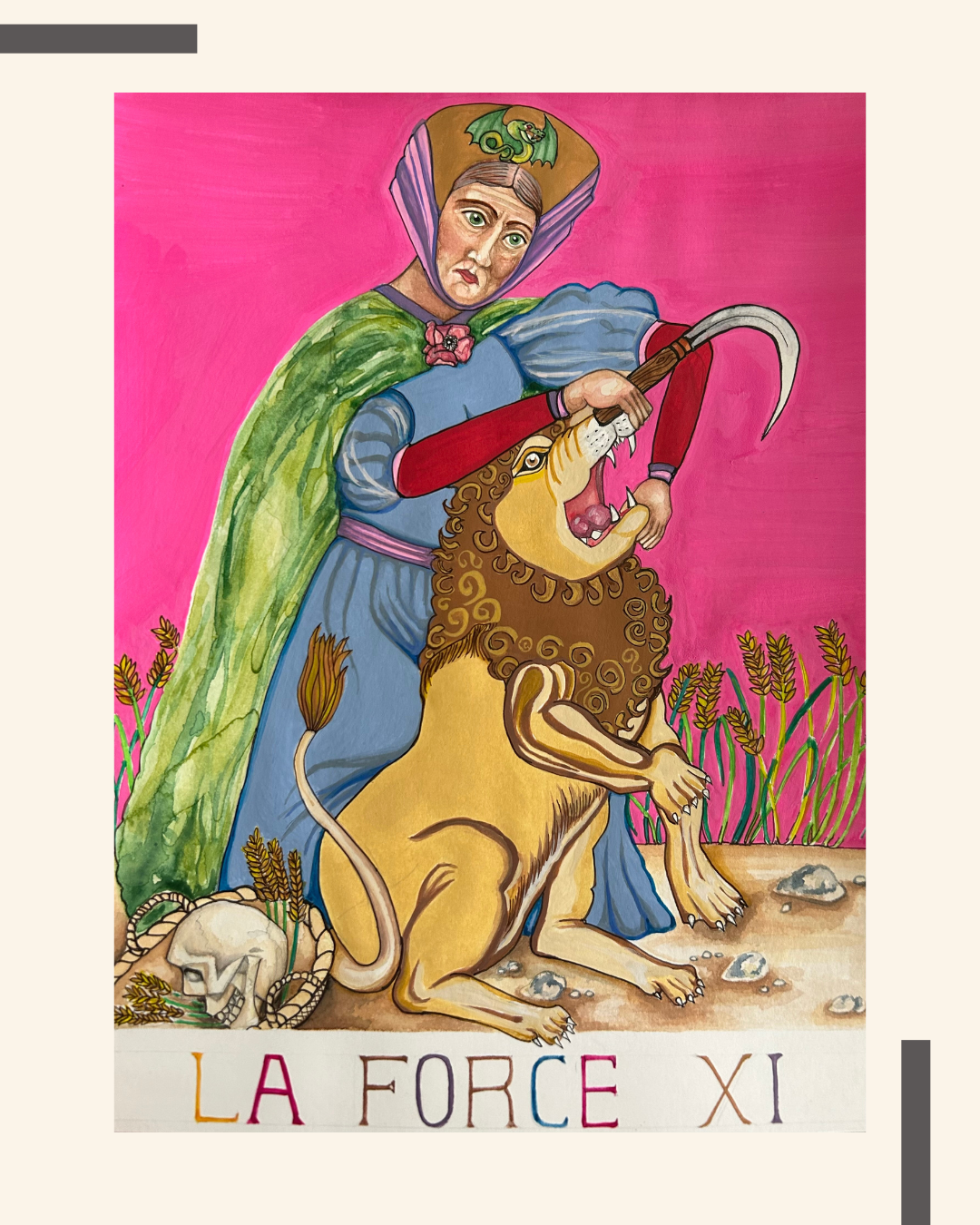

Like most academic writing, the final result is never about sales or any kind of acclaim — it’s enough just to see it out there in print. Dream achieved. What now? Well as wonderful as the entire process has been, last summer I found myself yearning to return to the central idea of historical menopause and the literary tradition but explored through a totally different lens. I wanted to put aside my logical and analytical side to dabble in something more creative and freeing. So, I returned to two of my first loves: art and the occult. The result has been an attempt to recreate my own original Tarot card pack featuring menopausal characters from my book. The first stage of the project is to render the Major Arcana cards, modifying the original images featured in the popular Rider-Waite deck.

What you have before you are these three: The Tower (card 16); Strength (card 11); and Justice (card 13).

The Tower and its Menopausal Shakespearean Meaning

Shit happens. I’m not talking of those natural organic processes of life where things fall away gracefully or poignantly and all “in due season” as Hesiod would say. I’m speaking of those sudden bolts from the blue — catastrophic, obliterating, so nuclear that one’s core being is shaken to its very foundation and nothing is the same ever again. Trauma, transformation, loss, be it spiritual, physical, material — the kinds of events that mendacious insurance brokers claim are ‘acts of god’. This is The Tower card. The woman falling is Lady Macbeth, the notorious queen from Shakespeare’s bloodiest of plays, Macbeth.